So school was in session at Krou Yeung School, and our yearlong stint as fulltime teachers — a position we never imagined we’d find ourselves in — was underway.

The first day we had to report at 7:00 to greet the parents who were coming for the official welcome back to campus. There were no classes that day — just kids playing with Legos and indulging in other kidly pursuits. Refreshments were served, and they included Cambodian “tamales”, stuffed with pumpkin and coconut, a treat that we could get ourselves addicted to rather easily.

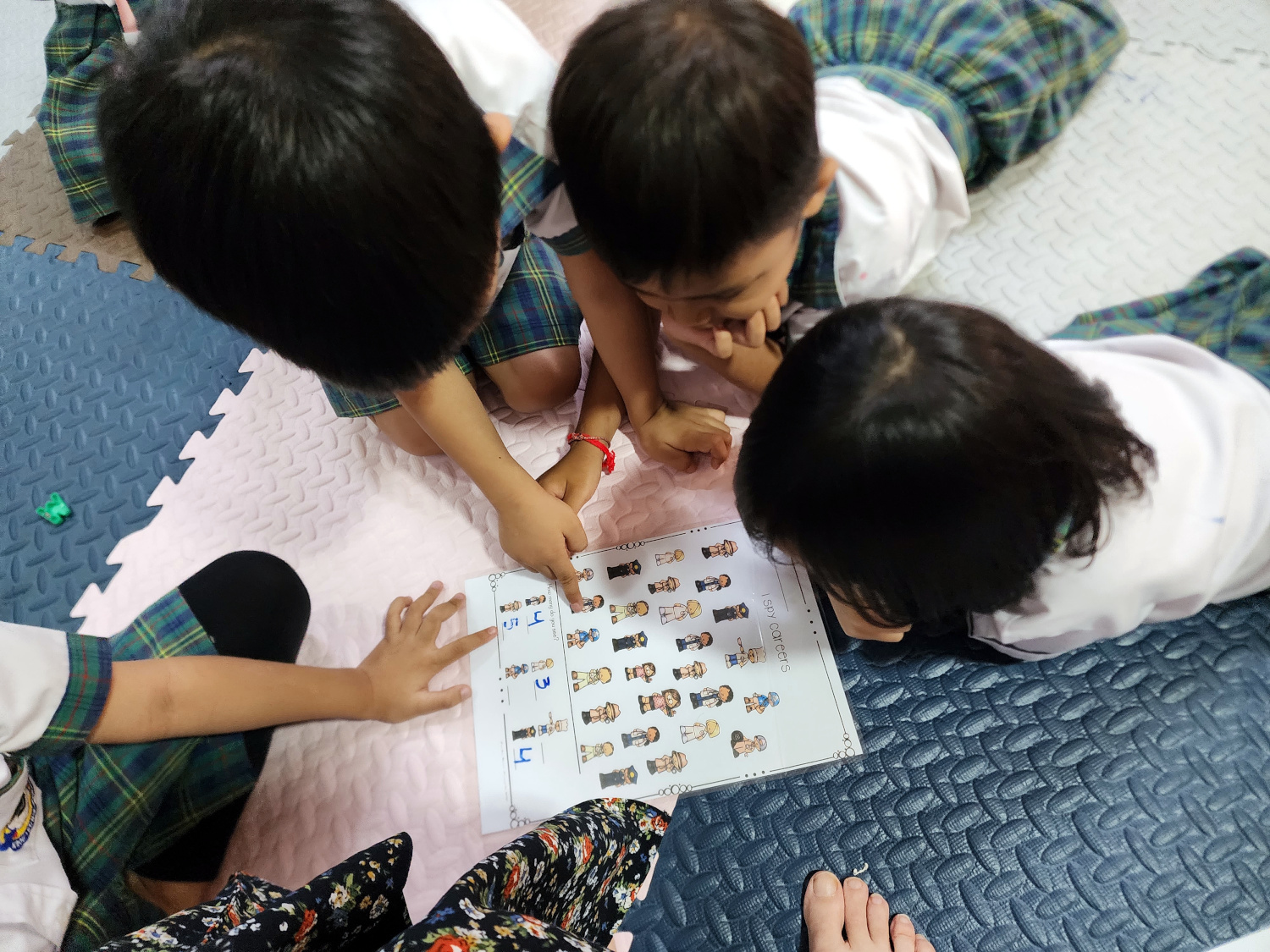

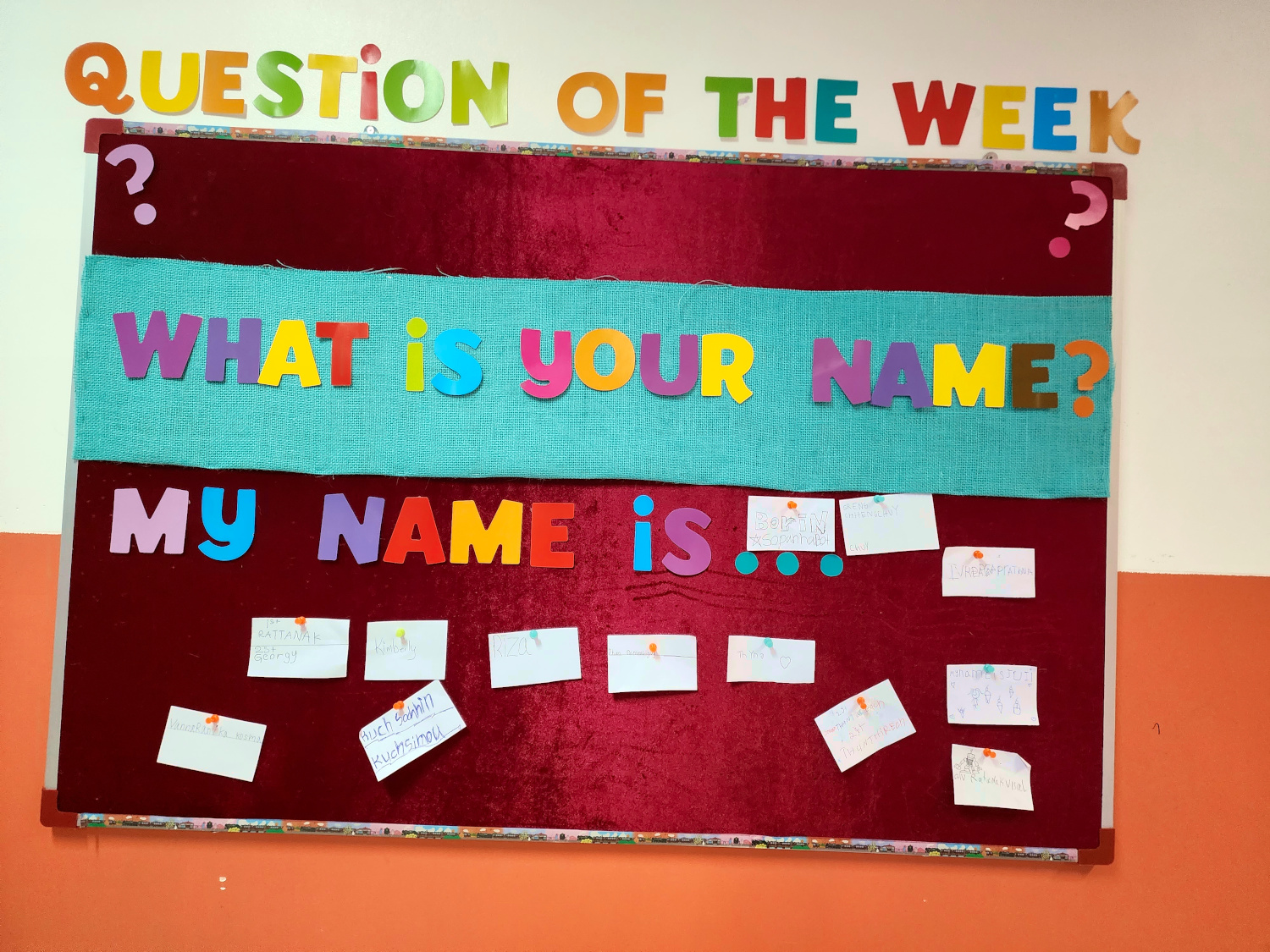

When classes did begin, Kimberly was teaching English to grades Pre-K through 2, and Dennis to grades 3 through 6. But his classes were all quite small — the largest was third grade with a total of 10 students, while Kimberly had 20 to 30 in her classes (since this is a new school, the majority of new students are younger, and they’ll work their way up the ladder). Plus, she had several students who were “on the spectrum”, and presented challenges that should have been handled by a trained specialist; but none were to be had.

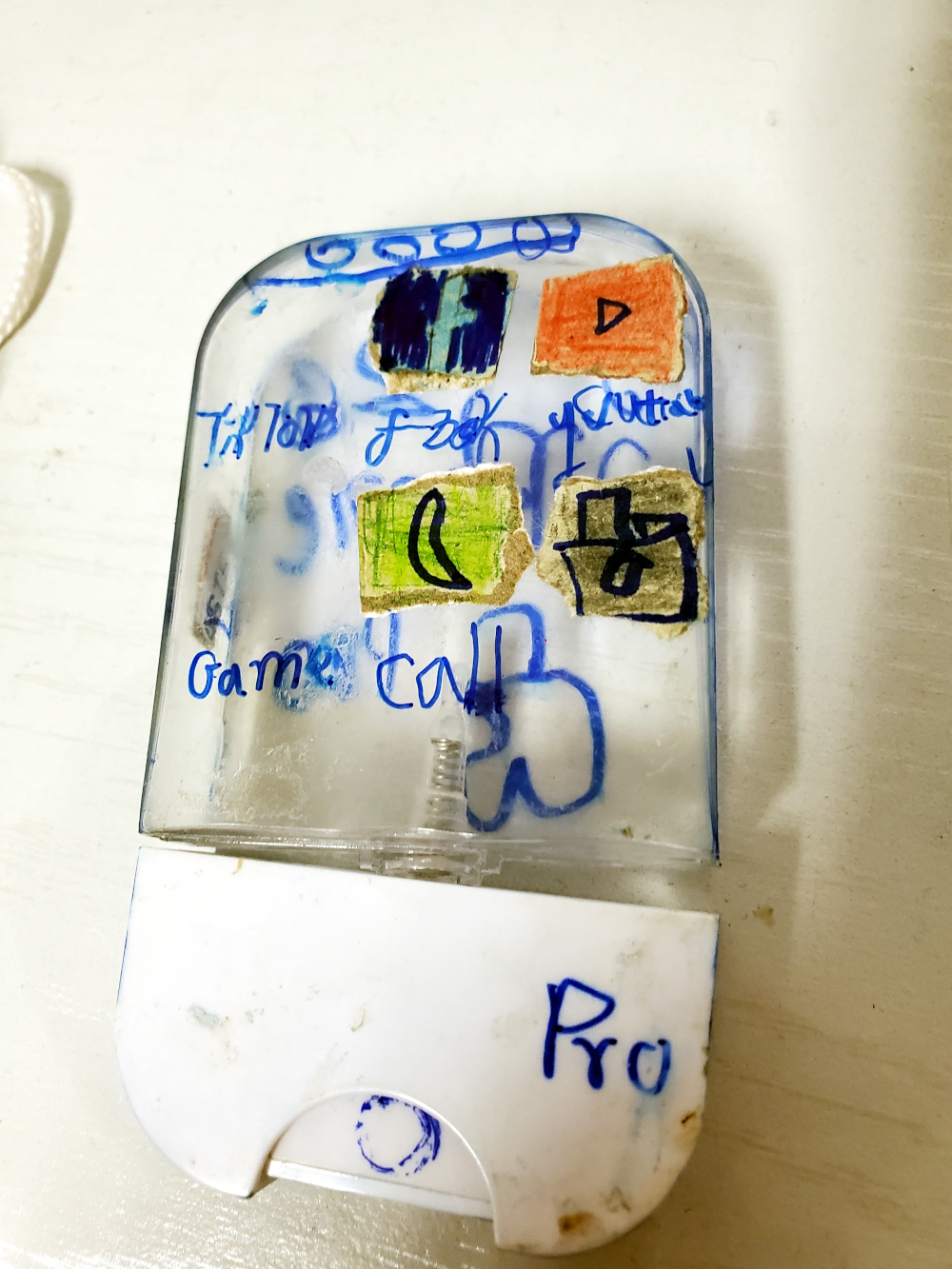

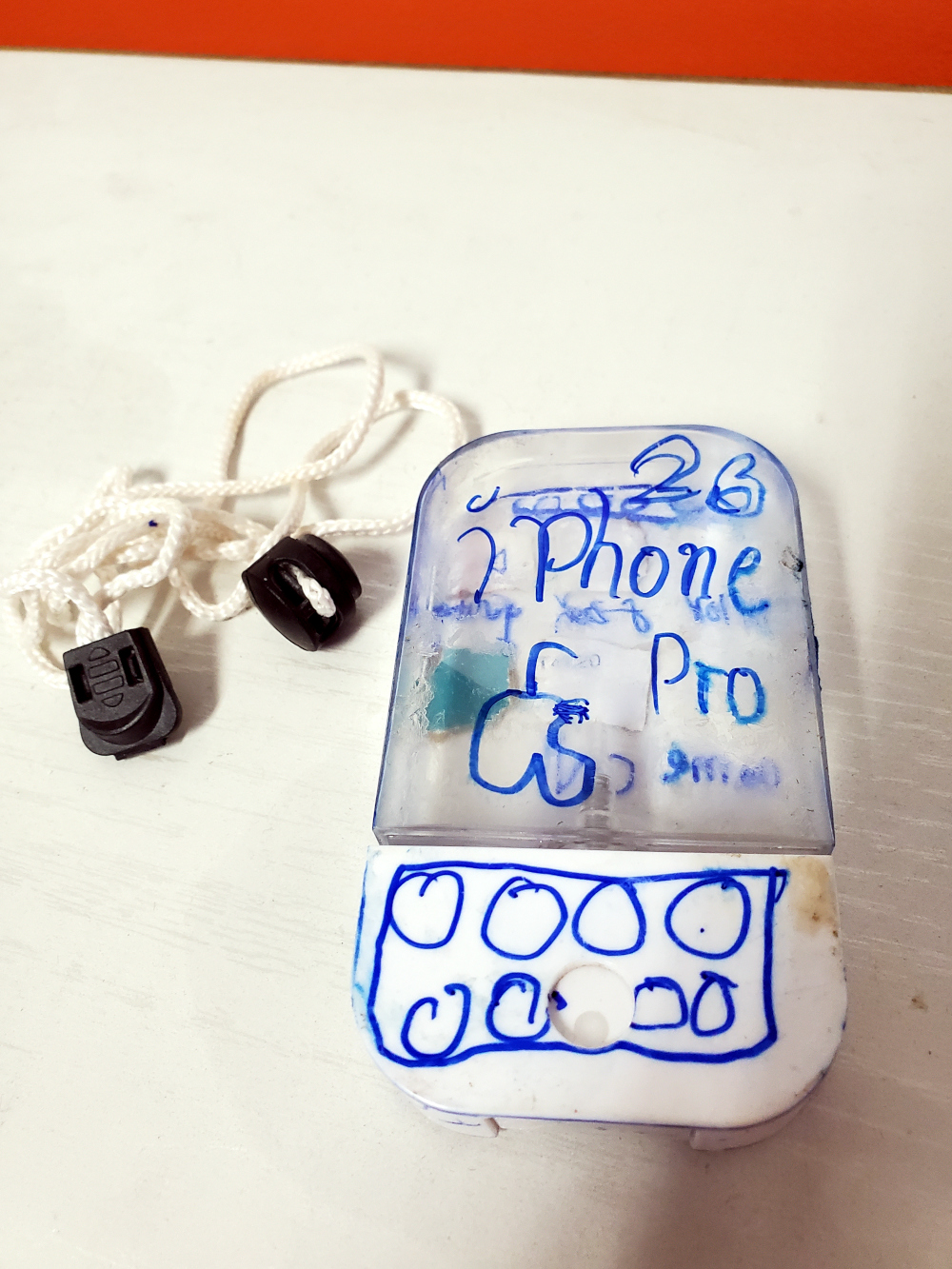

One of the third grade students (whom we were already familiar with from our volunteering at the school a few months earlier) brought Dennis a special gift: a “cell phone” he’d made from a plastic alcohol dispenser, complete with fake earphones. Freaking adorable.

Staff Meetings

Right off the bat, we had one of the periodic Saturday teachers’ meetings. Cambodian teachers have to put in some long hours, usually working on Saturdays as a matter of course. In our case, we were usually exempt from that requirement; and we didn’t always even have to attend the monthly meetings; but we thought it was important to do so this first time. And fortunately, there were two translators to explain the proceedings to us. We later attended other meetings at which someone droned endlessly in Khmer, and we had no clue about what was going on.

At this meeting, the subject of campus safety came up, because someone expressed shock over a recent school shooting in Thailand. ONE school shooting. In another country hundreds of miles away. We didn’t have the heart to mention that where we come from, school shootings are pretty much a routine weekly occurrence, often beginning with slaughtered children and invariably ending with a discussion of “gun rights”.

There was also a special meeting called on the next Saturday, supposedly to plan the events calendar for the coming year. It was intended to be about an hour meeting, but it dragged and on and on for three-plus hours. At one point we broke for lunch; not having brought any food with us, we asked one of the teachers (a really cool dude named Sela) if he knew of any place nearby to buy something that would keep vegetarians from starving. He instructed Dennis to follow him, and Dennis thought he was just going to step out onto the street and point out something. Instead, he led Dennis to the parking garage, and told him to hop on the back of his motorcycle (the preferred mode of personal transit for Cambodians).

And they were off, zipping through the streets. Dennis is, shall we say, not fond of motorcycles; and since he had no helmet, he was especially apprehensive about riding piggyback on someone else’s. Moreover, he had neither sunglasses on his face nor hat on his head, nor sunscreen on his skin; and being quite vampirish, he found that to be a bit unsettling as well.

They ended up at a vegetarian restaurant — of which there are quite a few in Phnom Penh, even though Cambodians are heavy carnivores — where Dennis did indeed find plenty of dishes that were quite satisfactory for him to take back for him and Kimberly. And he survived the return ride in one piece as well.

One day during this first week, a delegation came from Cambodian Children’s Fund, a charity designed to help educate Cambodia’s children and lift them out of poverty. With headquarters in Phnom Penh, it also has branches in Australia, Hong Kong, the UK and the US. When introduced to these visitors, we had a bit of a chance to practice our very shaky Khmer, which we’d been working on not nearly as much as we should have been.

Also during the first week, we received our brand spanking new work permits, in the form of sleek, sturdy plastic cards with our photos and text in both Khmer and English. Now we were really and truly official, at least for 4 months. The problem with Cambodian work permits is that they’re issued for a calendar year rather than for a span of time. So if you obtain one on December 31, you’ll need a new one the next day. And they ain’t cheap.

The school also gave us back “our” bikes, which actually belong to the school, but which we’d had use of during our previous stay. And this time we purchased helmets at a Decathlon, which is sort of the Asian equivalent of Dick’s Sporting Goods (but even better, for our money). They were a necessity with commuting to and from work every day in rush hour; rush hour in Southeast Asia is really and truly rush hour. If you’re not accustomed to it, the traffic (which mostly means motorcycles) is horrifying. But after a couple of weeks of navigating your way through it, you just learn to think like a native and go with the flow, assuming your own role in the multitudinous game of chicken. Amazingly, there are very few accidents.

Banking in Cambodia as an Expat

The school helped us set up accounts with the branch of ABA (Advanced Bank Of Asia) across the street, so they could deposit our paychecks directly. But it was quite a godsend for another reason. One of the headaches of being abroad is that when you buy something with a debit card, your bank tacks on a 3 percent fee. Sometimes the merchants will pile on fees of their own. Alternatively, you can withdraw local currency from an ATM; but your bank will still rake in 3 percent (except for those rare cases when you can actually locate one of your bank’s own ATMs in a foreign country), plus the bank the ATM belongs to will slap on its own fee of anywhere from one to TEN percent.

But having an ABA account eliminates all of that. Because 99.9999…. percent of the merchants in Cambodia accept ABA transactions with just a scan of a QR code. Even the vendors at little produce stands have ABA QR codes, though you have to enter the amount manually. And in all of these transactions, there are zero fees involved. It’s the most convenient and user-friendly banking and shopping arrangement we’ve ever had. (Many vendors do the same with accounts from Acleda and Wing banks, but ABA is far more common.) By the way, all Cambodian merchants accept U.S. dollars in payment as well as Cambodian riel, with no commission charged; in fact, the dollar is actually preferred, probably because it greatly simplifies the math. (One dollar is equal to about 4100 riel.)

Toul Tom Poung “Our” Neighborhood

So we were all set to be fully functioning residents, and to shop for our produce and a few other goods at nearby Toul Tom Poung (nicknamed “Russian Market”), which is a hive of local culture.

Not far away is Sacred Lotus, a vegan restaurant located in the lobby of a hostel, which served ample portions of excellent dishes at a very low price (by American standards). It became our dinner spot every Wednesday and Saturday (on Saturday, strangely enough, there was a 10 percent discount). This was a much welcomed ritual that helped us come down from our frantic week of dealing with classrooms full of youngsters.

9/4-30/2023

Leave a comment