Thanks to Stephen Speilberg, just about everyone has heard of Oskar Schindler. As owner of an enamel factory during the Nazi Occupation of Krakow, he is credited with saving the lives of hundreds of Jews by giving them jobs — and a place to live that was at least somewhat better than the concentration camp they otherwise would have been consigned to. The building where this all occurred still stands in Krakow. Part of it is an art gallery — you can spot an art installation outside that looks like a row of concrete bicycles — and part of it is a museum devoted to preserving the memory of the victims of the holocaust and the story of Schindler’s famous list (of which he actually had several). Naturally, while spending a week in Krakow between volunteering gigs, we had to tick the museum off our bucket list.

On a brisk Monday morning, we walk there from our Airbnb in Old Town Krakow, passing such medieval landmarks as the Barbican, over the Vistula River and into the part of town called Kazimierz, otherwise known as the Jewish Quarter. We arrive plenty early, but there is already a line, which will only get longer before we are inside.

It’s probably a longer than normal line, because Monday is a free day at the museum. It’s part of a consortium of attractions in Krakow that offer free admission on various days. So if you investigate this schedule and plot your itinerary accordingly, it can make the difference between spending a few hundred dollars (depending on the size of your party) and spending little or nothing,

After about half an hour, the doors open, and we get to go inside where it’s warm — probably warmer than the Jewish laborers had it back in the day. In the lobby there are lockers where we can stash our belongings that we don’t want to tote around for the duration. We opt to put our water packs in there, thinking we’ll only be touring the facility for an hour or so. But we’ll regret that move, as we end up being inside for 3 solid hours, and there is no drinking water available.

There are several floors of engrossing exhibits, all imaginatively presented. In some places, you watch video clips through through the window of a mock-up of an office or tenement; or through a hole smashed out of a brick wall. Some of the items are rather disturbing: there are photos of men being hanged; and there’s a cigarette case made of human skin. It’s a good bet the skin wasn’t donated voluntarily. The Nazis thought it was cute and clever to craft such handiwork.

The exhibit has a nice chronological flow to it. The depictions begin when life in the city’s Jewish Quarter was still relatively comfortable and safe, and quickly goes south after the troops roll in.

Among other things, the photographs offer an illuminating glimpse into the lives of the Nazis themselves. These and other photos can be viewed through a circular bank of antique-style stereoscopes. There are candid shots of the soldiers and officials caught off guard, smoothing their hair or performing other mundane tasks and gestures, and sometimes even looking downright bored.

Which brings to mind the famous phrase “the banality of evil”, coined by German Jewish philosopher Hannah Arendt. She applied the expression to her observation that evil acts are most often committed not by people who are inherently and thoroughly evil, but by ordinary folk just “doing their jobs” and not questioning the moral ramifications of what they are called upon to do. It’s a concept we’d all do well to keep in mind.

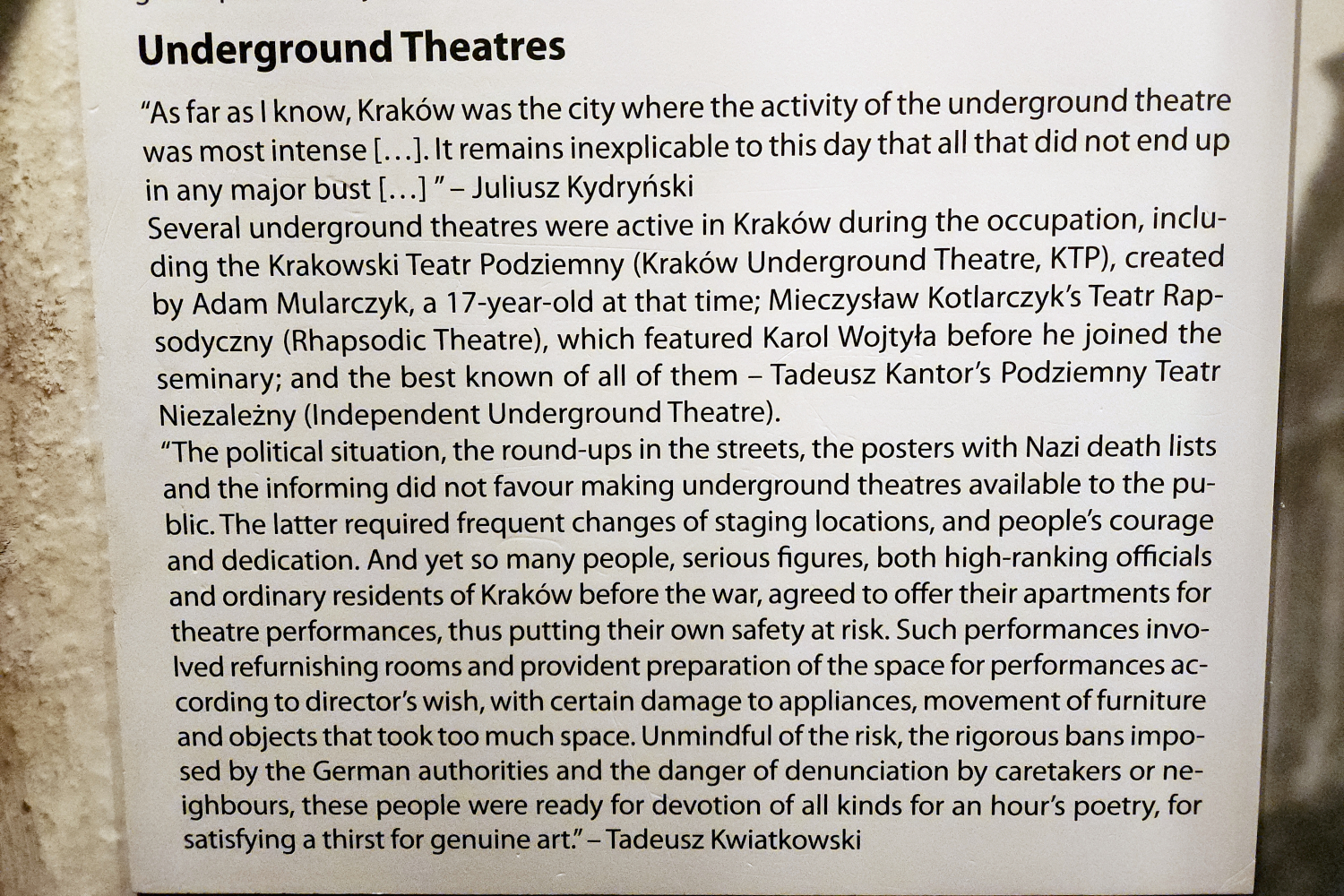

Amid all the grim reminders, the museum also offers a few mementos of joy, hope, and defiance in the face of brutalization. There are promotional materials for a circus that came to town during the height of the occupation, And relics of the “theatre underground” that operated — as former theatre creatures ourselves, the very concept of taking theatre underground and using it to thumb your nose at oppressive authority sounds just positively delicious. Although these individuals operated at the risk of their lives.

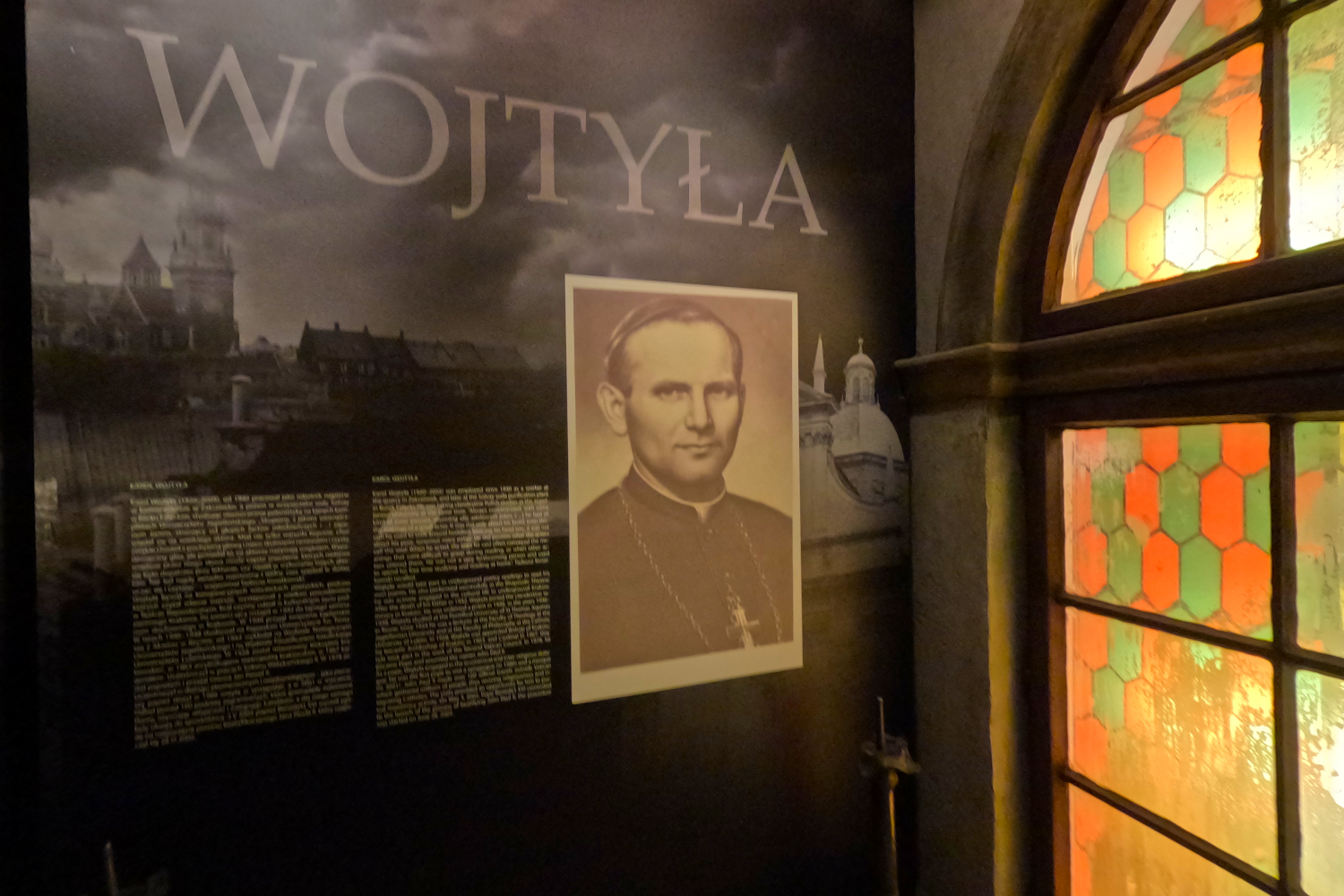

One of the brave co-founders of this movement was local boy Karol Wojtyla — who at the same time attended an underground seminary, and in later years assumed his most famous role as Pope John Paul II. (In Dennis’s days as an actor in San Francisco, he performed in the West Coast premiere of Wojtyla’s play “The Jeweler’s Shop”. Which was presented not only above ground, but on a hill.)

It isn’t until fairly late on the self-guided tour that we finally encounter Oskar Schindler himself. His desk is on display and his office is restored, near a glass showcase of some of the pots and pans his factory turned out.

We’re glad to see that the museum is honest in its appraisal of Schindler’s character, perhaps more so than Speilberg’s film. History that glosses over the warts is not really history, but mythology or even propaganda. Americans have a tendency to apotheosize their historical figures at ridiculous lengths; the founders of the nation are often portrayed as demigods who never lied, cheated, doubted, slacked off, or even went to the sandbox; history books, at least traditionally, rarely if ever mentioned that they literally owned other human beings.

But flawed people (which we all are) can still do great things when they meet the challenge. And Oskar Schindler did. He was a scoundrel with a history of indulging in bribery and other shady business practices. In fact, he assumed ownership of the factory only because the Nazis seized it — and he was, lest we forget, a Nazi himself. Initially, he used Jewish labor just because he didn’t have to pay them anything.

But somewhere along the line, he developed a heart and a soul, and began to genuinely care for the people he rescued from death. Previously having acted always out of self-interest, he gradually started risking his safety, wealth and social status to save lives — ultimately, he even spent all of his own money in the cause.

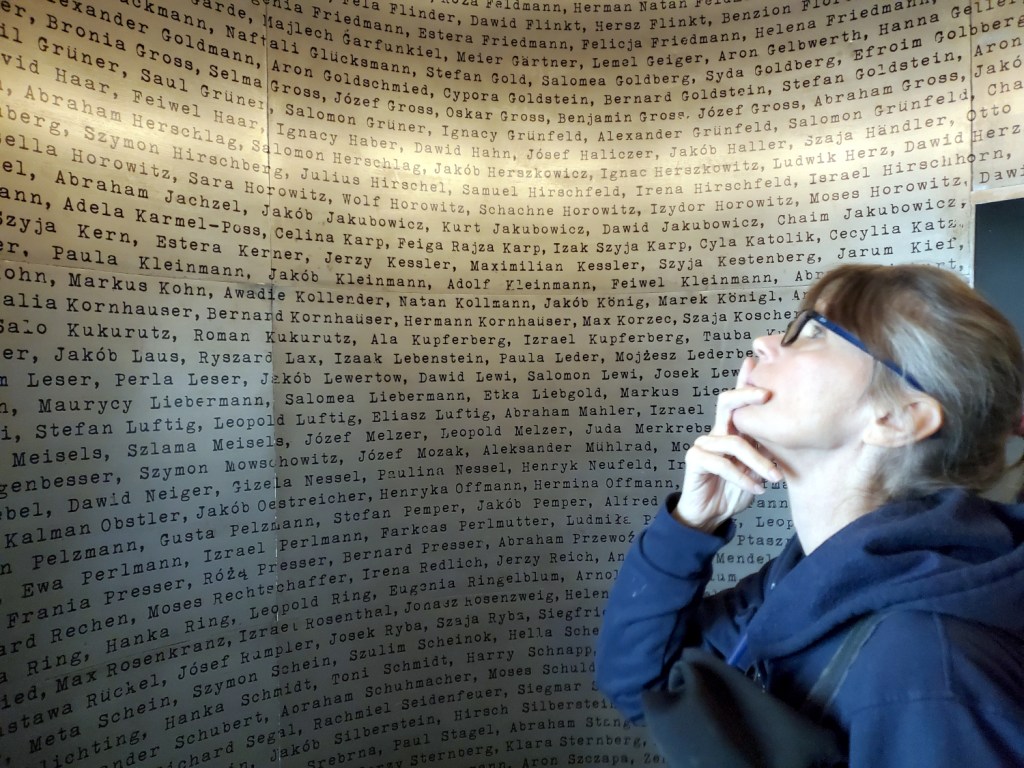

And because he rose above himself, the 1200 names appearing on the wall of his former factory represent individuals who, instead of being counted among the millions lost, were able to live to tell their stories.

Events occurred: 2/24/2025

Leave a comment