The big day has arrived in Athens. We finally are set to see the biggest draw in this timeless ancient city, the Acropolis. It’s been on our bucket list for many years. And when we finally are walking on its grounds, we discover that it measures up to every bit of its hype.

When we get in the line at the entrance, we’re beginning to fear, based on exchanges we’re hearing at the window, that we’ll have to make an appointment to return at another time or even on another day. But this turns out not to be the case. We elect to purchase passes to 7 local attractions for 30 euros per pass, which is also the admission for just the Acropolis itself. Go figure.

Fearing that the wind will climb higher and the temperature plunge lower as the day grows longer, we make our way straight toward the top. But we can’t resist pausing to admire the Theatre of Dinoysus, and then the Odeon of Pericles, (which is another theatre built next door about a century later and now mostly in ruins). But the former, constructed in the Sixth Century BCE, was apparently the birthplace of theatre as we know it; so you can only imagine the awe that we feel standing in front of it. Here we are, a pair of former thespians who spent decades toiling in theatre ourselves. now back at the very roots of our former profession.

Dedicated to Dionysus Eleuthereus, the god of wine, fertility and theatre (that’s quite a gamut), the structure was originally wooden, but within a couple of centuries the wood had been supplanted by stone. Spring festivals honoring this deity included the performance of scripts written by the likes of Aeschylus, Euripides, Sophocles and Aristophanes.

Quite a coincidence that this town, and especially this same neighborhood, would be the birthplace of both modern theatre and democracy, eh? Well, no. It’s not a coincidence at all. The two developments are closely intertwined. Originally, theatre largely featured single figures, representing gods and legendary personae, addressing the audience, just as a ruler would — a reflection of the top-down thinking that governed civilization at that time, giving us religion, tradition, and oligarchy. But then someone came up with the brilliant innovation of having characters on the stage address each other as well, resulting in what we call dialogue. Furthermore, members of the audience served as chorus, and as judges for theatrical competitions. The spectacles onstage often dealt with ethical and moral issues, in which the public had a voice. It was only a matter of time until this kind of dialogue seeped into real life as well. And that led to the bottom-up thinking that gave us philosophy, science and democracy.

By the way, this theatre is still used for concerts, and stone seats have been installed in recent years. Stone? We’ll bring along our own seats, thank you.

And then it’s up to the top, the seat of the gods from which the top-down thinking was dispensed. Even the entrance to the hilltop is awe-inspiring and just plain inspiring. The stately columned archway is known as the Propylaea, or gateway, and it’s a good intimation of the splendors that lie farther up on the hilltop. The crown jewel is the Parthenon, built in the 5th Century BCE as a temple dedicated to Athena, the goddess of wisdom for whom Athens is named. It also served as the headquarters of the treasury.

Nowadays we’re accustomed to seeing the Parthenon in its state of near-collapse. But less than 400 years ago, it was in a much more complete condition, much closer to the way the ancients left it. But in 1687 a massive explosion of an arsenal being stashed there caused more damage than Father Time had wrought in all his centuries. And since then, the painstaking process of putting Humpty Dumpty back together again has been crawling along. At various places on the hilltop, you can see bits and pieces of the structures, waiting to be sorted and fitted back where they belong, a scrambled stone Lincoln Log set.

The Acropolis has had to survive not only the ravages of time, but the ravages of human stupidity and callousness. In 480 BCE the Persian army (who, by the way, wore garments not unlike modern trousers) invaded and devastated the city of Athens, after the inhabitants had fled for safety. The Parthenon had not been built yet, but there were temples and statues on the Acropolis and elsewhere, which the marauders burned, smashed and toppled with wild abandon.

Much more recently, between 1801 and 1812, a crew engaged by the British “nobleman” Thomas Bruce, 7th Earl Of Elgin, stripped the Parthenon of many priceless statues and hauled them back to England, where they remain to this day. Lord Elgin claimed he had permission to remove these relics, though no authentication of that claim has ever been found. They have become commonly known as the Elgin Marbles — except in Greece, where they’re the Parthenon Sculptures, thank you very much. This whole incident is a sobering reminder that all too often, history does not favor the good, the noble, the constructive; but confers much more fame and glory upon the ruthless, the egotistical, the plunderer, the exploiter and the despoiler. (Christopher Columbus, for example, has his own holiday today, even though he was imprisoned upon returning to Spain for his horrific abuses of the New World natives; but nobody remembers Bartolome de las Casas, the priest who documented and reported the atrocities.) Far more people are familiar with the name Elgin Marbles than with the name Phidias, the sculptor who directed their creation — or with Ictinus and Callicrates, the architects who designed the Parthenon.

Going back through the gateway and down the hill again, you come to a much lower hill known as the Aeropagus (Hill Of Ares — so named because the war god supposedly was put on trial here). According to legend, the apostle Paul of New Testament fame delivered a speech on this hill, though that’s dubious. What is known is that the celebrated Athenian orator Isocrates gave a famous speech here that has come to be known as the Aeropagitica — a title borrowed centuries later by the great British poet John Milton for an influential treatise he wrote defending freedom of speech and decrying censorship..

After seeing the Acropolis, we stop on the way home to check out the Roman Agora, which was the “newer” of the two civic centers of the ancient city. The older, bigger, and better known agora is on the schedule for the next day. The Roman Agora was built to supplant that one just before the turn of the millennium under the direction, and the ka-ching, of Augustus Caesar when the city was under Roman domination.

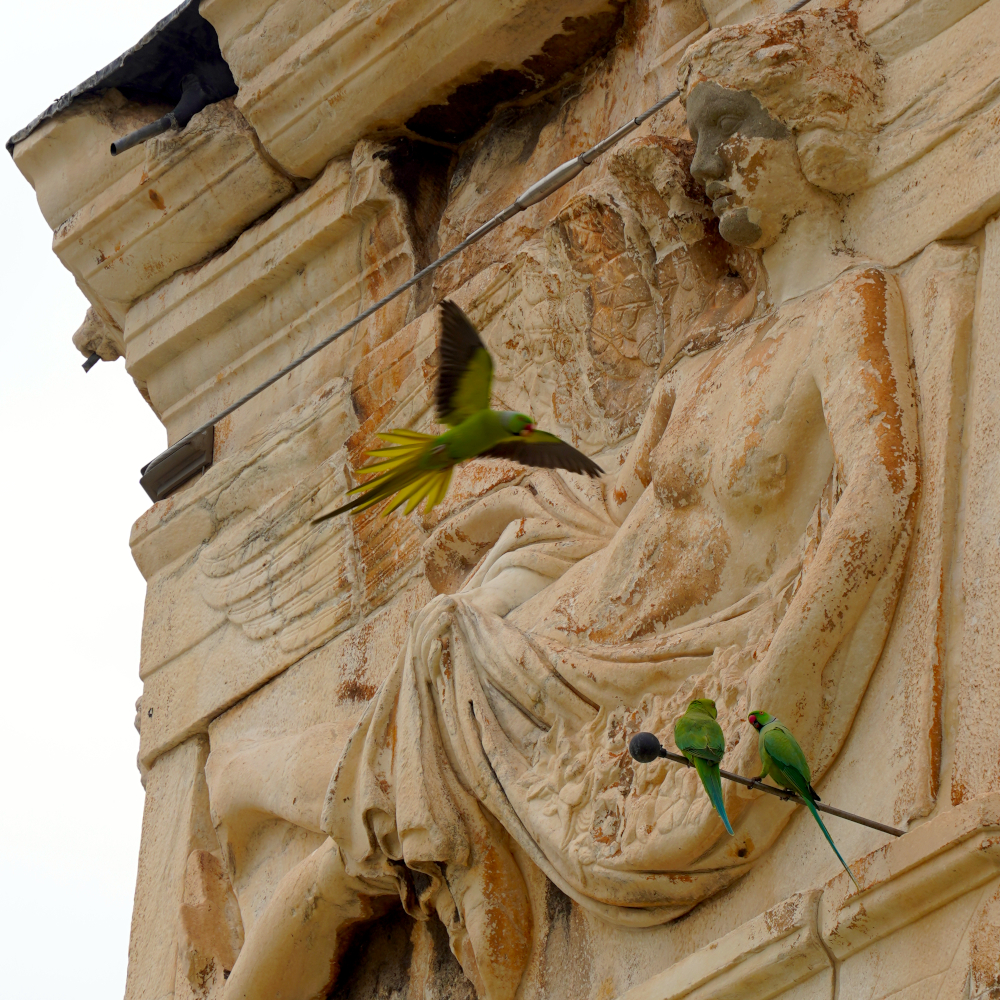

The most interesting feature of the Roman Agora is the Tower Of Winds, which is one of the few ancient structures surviving essentially intact. An octagonal tower 39 feet high, it housed a water clock, and its exterior is sculpted with personifications of the “eight winds”.

Okay, so having spent the better part of one day exploring the “top-down” center of the ancient city, we’ll be devoting the next day to the “bottom-up” center, the Ancient Agora, which was the seat of government and thus the cradle of democracy, as well as — not at all coincidentally — the forum in which the western world’s greatest thinkers taught their philosophy.

We’re in the middle of a bucket list stop with many very impressive buckets.

Events occurred: 2/11/25

Leave a comment